Mar

The conversation isn’t over

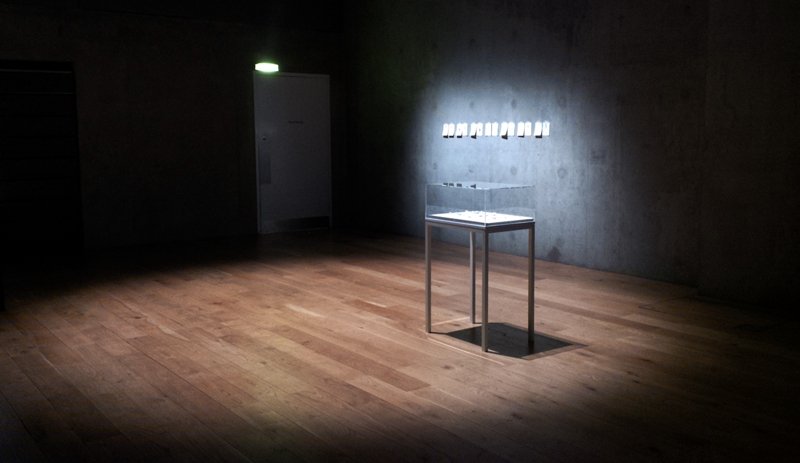

Last winter, Nottingham Contemporary presented the Monuments Should Not Be Trusted exhibition that explored “the golden years” of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia through the works of over 30 artists from this period and location.

As part of the yearly Memory Project, now called Aftermath, students from the Master of Fine Arts from Nottingham Trent University and for the first time, students from the MA History of Art and MA Visual Culture from the University of Nottingham, collaborated to create an exhibition that responded to Monuments Should Not Be Trusted by reactivating the conversation that started with the winter show, and even half a century earlier in Yugoslavia.

We named it The conversation isn’t over and it was a new experience for most of us, which on the one hand was the cause of some logistical problems, but on the other hand gave us a taster of what our career as (hopefully) artists and curators would be like.

I made a piece of work specially for this exhibition and showed an older one I made in October at the beginning of the course.

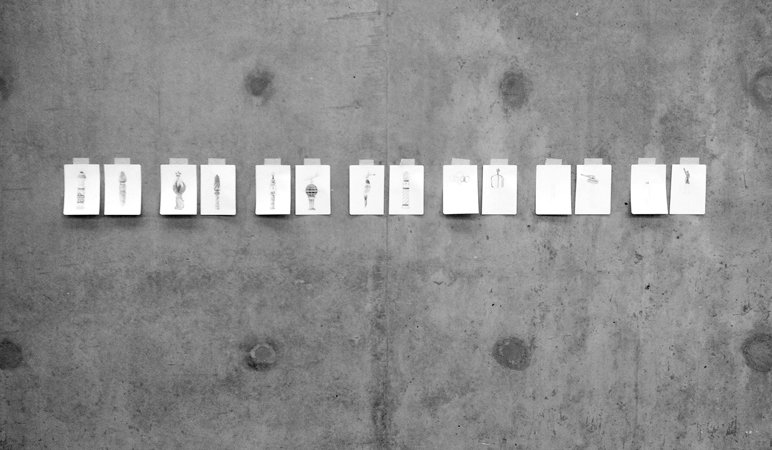

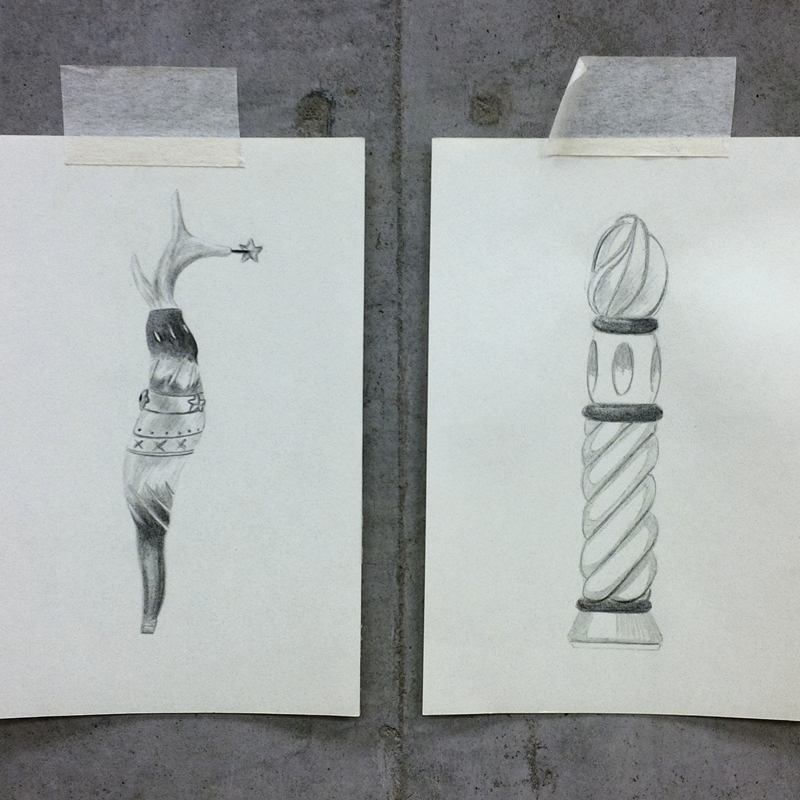

Tito’s Dildos is a series of 14 pencil drawings directly inspired by a collection of relay batons presented in Monuments Should Not Be Trusted. These relay batons are part of a (much) larger collection of dozens of thousands batons used in the Relay of Youth races, organized from 1945 to 1988 as a celebration of the Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito’s power and birthday. The Youth Batons were, in other words, birthday gifts from the people of Yugoslavia to their leader, who was sometimes depicted as benevolent, yet referred to as a dictator.

This major contradiction led me to the humorous reinterpretation of these beautifully crafted objects as dildos.

Because of their phallic shape, the sex-toys can be seen as symbols of male authority but are commonly associated with female masturbation and homosexuality, which are far from corresponding to the representation of hegemonic masculinity cultivated by dictatorships.

By (imaginarily) shifting the original batons’ use, we are opening the gates to reinterpretations of history where for example, Tito would be a collector of fanciful dildos, or the people would openly tell their leaders to literally ‘go fuck themselves’.

These side stories obviously only exist on these pages from a personal diary, the closest antithesis I found to propaganda posters.

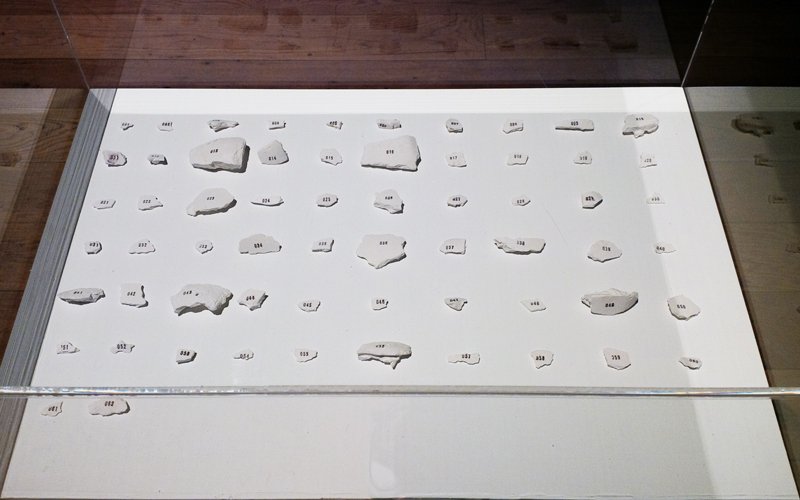

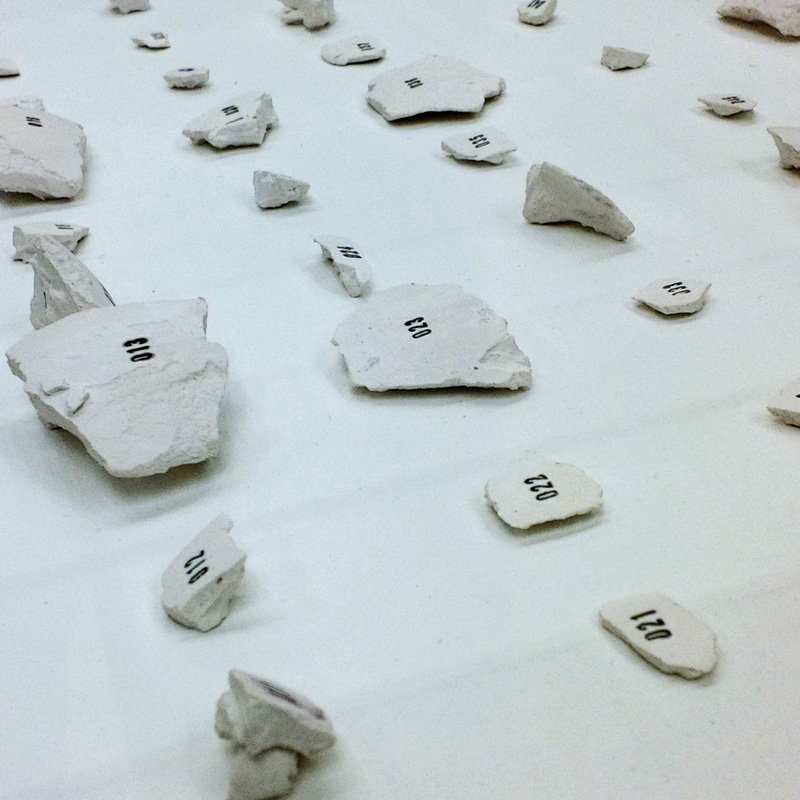

Artefacts bears a more solemn aura. It is made of 62 pieces of plaster stamped with numbers from 001 to 062 and sorted by ascending numerical order on a grid of 7 rows and 10 columns.

The fragments are presented as archeological findings but don’t seem to be pieces of an identifiable object. They rather seem to have been chosen at random, and order only comes from the numeration that looks just as arbitrary as the small sculptures’ shapes.

Archeologists excavate and decipher fragments of human history, a common heritage to us all. By acknowledging these Artefacts as pieces of art, you are making them a picayune part of this heritage, one that is yet to be unravelled.

This third artwork, a ready-made from Inferno Pizza, wasn’t displayed for security reasons. It was part of a performance I called Relishing Aftermath.